How mainstream online tools are exposing us to gangs, stalkers, and abusive exes

Julia had been dating her partner for about a month when the abusive phone calls began.

The partner had warned Julia when they got together that he had a stalker: a former girlfriend intent on sabotaging his life. But neither expected the woman to find the phone number for Julia’s family home and threaten her relatives with violence.

Soon Julia was being bombarded with emails, texts, and even a Venmo request with a note claiming to have “pornographic evidence” of her partner’s infidelity. The woman walked past Julia’s house, confronted her outside a McDonald’s, drove a nail into her car tire.

But how did the stalker know where to find Julia, who barely used social media? During a brief encounter, she got a worrying reply: “I found your info online.”

That was how Julia, a white-collar worker in her thirties in the U.S. northeast, discovered the shadowy and barely-regulated industry of data brokers. When Julia searched her own name, and paid a small fee, she found her “whole life story”: where she went to college, her past addresses, the names of her roommates and closest friends.

“It was shockingly personal, and made me feel incredibly vulnerable,” Julia, who asked to be identified by an alias, told The Independent.

Even if you don’t know data brokers — and most Americans don’t, according to a recent survey — they almost certainly know you. These companies compile vast amounts of public and private information that they then sell on to customers.

Some of this data comes from public documents such as marriage certificates, drivers’ licenses and voter registrations. But bank records, loyalty cards, internet browsing histories, and even braking and acceleration logs from internet-connected cars are also sold to brokers by the collecting companies (often via a complex web of intermediaries).

The U.S. has no comprehensive nationwide privacy laws, meaning data brokers are barely regulated at the federal level and only partially in some states. Hence, experts say there are often minimal safeguards against people exploiting them for ill ends.

“We see data broker information used as a tool of abuse with alarming frequency, especially in stalking and coercive control cases,” Belle Torek, of the National Network to End Domestic Violence, tells The Independent.

“An abusive partner or ex doesn’t have to be particularly tech-savvy: they can easily Google a name and suddenly have an address, relatives, work history, and other identifiers that [they] can use to dox, harass, impersonate, and intimidate survivors.”

The consequences can be devastating. In 2020, a disgruntled attorney named Roy Den Hollander broke into the home of New Jersey federal judge Esther Salas disguised as a FedEx delivery man, killing her 20-year-old son Daniel Anderl and critically injuring her husband Mark before taking his own life.

Salas said in a statement that Den Hollander, a self-described “anti-feminist”, had used data brokers to assemble “a complete dossier” on her family, including her address and route to work.

More recently, an FBI affidavit stated that Vance Boelter — accused of murdering Minnesota Democrat Melissa Hortman and her husband Mark last June — possessed a notebook listing 11 data broker sites and their offerings. (The affidavit did not say whether Boelter accessed the sites.)

U.S. immigration authorities have also bought domestic flight data and cell phone location data from brokers to help track down undocumented immigrants, reports by 404 Media have claimed.

“It is safe to assume that data brokers have personal information ranging from your name, address, and phone number to your geolocation, political beliefs, and sexual identity,” Sam Adler, co-author of an upcoming academic paper on how data brokers endanger abuse survivors, told The Independent.

An ‘uncontrollable beast’

In October 1999, a 20-year-old dental assistant named Amy Boyer was shot dead in Chicago by a stalker who had bought her details from a private investigations company.

It was an early sign of how dangerous society’s ever-increasing accumulation of digital data could be in the wrong hands.

There are at least 750 data brokers in the U.S., according to digital rights group Privacy Rights Clearinghouse. They range from tiny, fly-by-night firms on strip malls to globe-spanning titans with Park Avenue headquarters.

“People search” websites, such as industry leaders Spokeo, WhitePages, and Intelius, allow practically anyone to look you up for a small fee (sometimes less detailed searches are free). Meanwhile, credit reporting giants such as Experian, Equifax, and TransUnion and data crunchers such as Acxiom, Epsilon, CoreLogic — the largest by revenue, according to data deletion service OneRep — limit their products to business customers such as marketers, banks, debt collectors, and realtors.

CoreLogic, Experian, Equifax, Epsilon,, Intelius, Spokeo, WhitePages, and the Association of National Advertisers did not respond to questions from The Independent. The Consumer Data Industry Association, an industry lobby group, declined to comment.

The industry says its services are crucial for businesses to verify customers or run background checks, as well as for law enforcement investigating crimes. They also help journalists check facts and find sources. (Like many news outlets, The Independent uses legal information provider, LexisNexis, to search public records.)

Some parts of the world have robust laws limiting this trade, such as the European Union’s GDPR. But only 20 U.S. states have similar “comprehensive” data laws — and none are as strong as GDPR, according to the Center for Information Policy Leadership.

State DMVs are explicitly permitted by law to sell personal data. Cell phone carriers, payment providers, car companies, menstrual tracking apps, and an app for tracking a child’s location: all have sold users’ data to third parties, according to media reports and academic studies.

Some of this data is incredibly sensitive. The World Privacy Forum, a non-profit campaign group, testified before Congress in 2013 that it had found brokers offering lists of rape survivors, seniors with dementia, HIV/AIDS patients, and potential alcohol or drug addicts.

In theory, that kind of data is usually restricted to business clients who must agree to only use it in certain ways. “We have extremely strong controls to protect the data we hold, and we carefully vet potential customers,” a LexisNexis spokesperson told The Independent.

“Our databases are not available to the public; only to verified entities… after a thorough credentialing process. We audit customers, mandate customer training on how to use data legally, and monitor data usage to identify potential abusers.”

Acxiom said it does not offer data to the general public, nor allow its customers to look up specific individuals, and that all its data is “ethically sourced” from “publicly available information and trusted sources”.

TransUnion said all its customers “are bound by rigorous contractual agreements and must certify that they have an appropriate use for the product.”

But not all brokers make such efforts. A 2023 Duke University study found “seemingly minimal vetting of customers and seemingly few controls on the use of purchased data”, while Adler — a doctoral student at Fordham Law School — says the industry has practically zero safeguards against misuse.

“These companies are largely unregulated and have no incentive to inquire about their users or make it more onerous for them to quickly and frictionlessly purchase data,” Adler argued.

Turquoise Williams, executive director of Just Stalking Maryland Resources, said when you combine a dangerous obsession with this level of access to someone’s personal life, the consequences can be terrifying.

“It seems to be this beast that is uncontrollable,” Williams, a survivor of a violent stalker, told The Independent.

‘I live in perpetual fear’

It has been four years since Julia’s ordeal began, and the stalking continues to this day.

“I don’t give my phone number out for almost anybody, and I live in perpetual fear of my data leaking out,” she told The Independent. “I have extreme anxiety now… I’ve kind of stopped being forward and making new friends…I don’t really go out that much anymore.”

She is far from alone. According to Meghan Land, executive director of Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, data brokers have been a “common subject of complaints” to her group for “many years”, especially for victims of abuse, identity theft, and fraud.

“Victims can see the unsuccessful result of what are often great efforts they’ve undertaken to protect their information,” Land told The Independent.

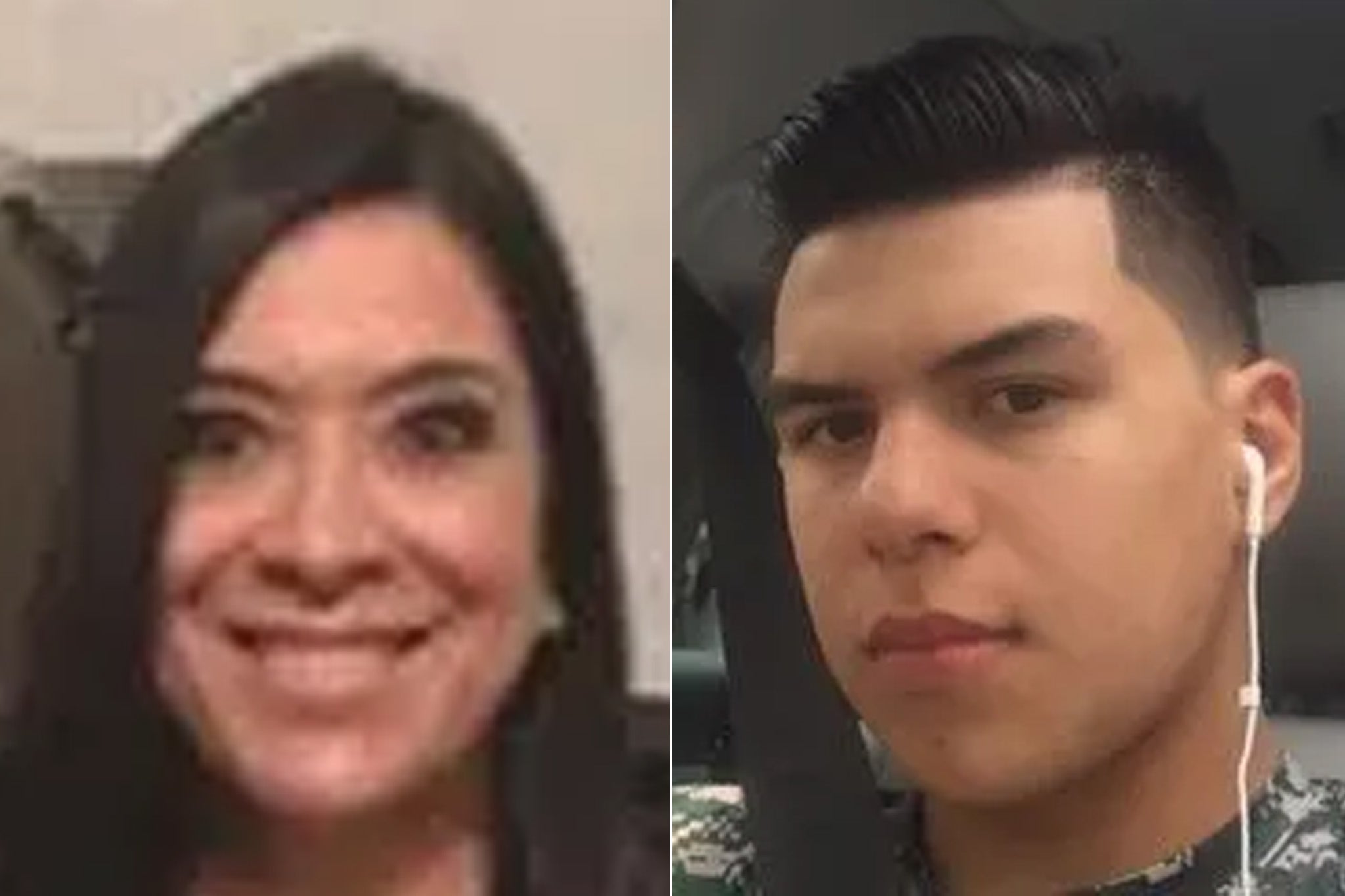

Jessica Tunon, a financial consultant in her forties in Washington, D.C. and founder of the wellness firm Netwalking, similarly believes her stalker was able to track her by using data brokers even as she relocated multiple times.

“I always felt like I was being followed,” Tunon told The Independent. “There was never a time when I didn’t feel like someone was watching me. Being on high alert for that long definitely affected my health, my wellbeing, my stress.”

The stalking continued for 13 years, and only stopped when she got a lawyer involved.

It’s not just abuse survivors who are put at risk. In 2020 and 2021, three brokers — Epsilon, KBM, and Macromark — admitted knowingly supplying information on millions of vulnerable elderly people to scammers who defrauded them of savings, according to the Justice Department. Two Epsilon employees were later jailed.

Last year the data removal service Atlas, on behalf of roughly 20,000 New Jersey law enforcement workers, filed class action lawsuits against 118 data brokers for failing to stop selling their information under Daniel’s Law (named in honor of Judge Salas’s son).

One police officer, who had helped take down an organized crime group, discovered the criminals had hired a private investigator to get her address from data broker websites and taken night-time exterior photos of her child’s bedroom window, one lawsuit alleged.

Another officer was targeted by an online influencer whose fans allegedly got his details from data brokers then spread them online, leading to death threats and a neighborhood visit from two armed, masked men.

‘A burden on your daily life’

Many data brokers say that individuals can opt out of having their personal information shared. But research suggests these requests are not always honored — and if they are, sometimes the information reappears within months.

“It is extremely challenging,” says Hayley Kaplan, a privacy consultant who helps celebrities, police officers, judges, rape victims, and others, scrub personal information from data brokers. “Sometimes you can’t reach anybody. They have phone numbers that are disconnected. Contact forms that don’t work. [And sometimes], when you do reach them, they’ll say ‘no problem!’, but then not actually do it.”

Muriel, a rape survivor who asked to be referred to by an alias, told The Independent: “I find a lot of them to be incredibly dodgy and shady…. sometimes they’ll just flat-out lie to you.”

Even when brokers remove personal data, it takes ongoing efforts to keep it offline. One woman quoted in Adler’s paper described it as “like playing whack-a-mole… a burden on your daily life.”

Adler and his co-authors propose a centralized, government-maintained register of people who’ve opted out, putting the onus on brokers to obey or face penalties.

The industry would probably resist that, just as it reportedly lobbied hard against Daniel’s Law and California’s DELETE Act, which gives consumers more power to opt out of having their data shared. The World Privacy Forum, the campaign group, describes past self-regulation efforts by the industry as “lacking credibility, sincerity, and staying power”.

For now, those endangered by the sale of their data must rely on patchwork regulation. California, Vermont, Texas, and Oregon all require data brokers to delete data upon request, though privacy advocates say there are loopholes.

Some people try to minimize their online footprint using P.O. boxes or state-backed home address confidentiality programs. Some 40 states offer such schemes, according to the Safety Net Project, although scope and eligibility vary.

Paid services such as DeleteMe, Optery, and EasyOptOuts can also help by automatically submitting opt-out requests to data brokers on your behalf. But these cost anything from $20 to $250 per year for one user, and they’re rarely comprehensive.

“I don’t make a ton of money,” says Julia. “[But] I have to pay for a lot of different services. The data cleanup services, the burner phone services, the misdirected package services. It’s expensive and anxiety-inducing.”

As for the brokers, her opinion is frank. “I think [they’re] the scum of the Earth.”